https://wildingout.substack.com/p/13-microfeminism-hacks-to-hilariously

Jan 29

“But tell us again how women are too emotional for …”

“Women can give birth. Women regulate and manage their emotions far better than men. Women tend to be less power hungry and corrupt in politics than men are. Women are far less likely to abuse children, both physically and sexually. They commit far fewer rapes than men and account for only 1 to 2% of all mass shooters.

“But tell us again how women are too emotional for __________.”

from https://themouthyrenegadewriter.substack.com/p/traitor-trump-is-waging-a-sexist

Jan 13

Objectification and Self-Objectification are Integral to Male Domination; Additionally, these Androcentric Realities are Related to the Ongoingness of Rape, by Jocelyn Crawley

As radical feminists continue to engage in acts of strategic resistance designed to engender awareness regarding the deleterious harms engendered by androcentric thought and praxis, many individuals become weary of ongoing academic discourse regarding the role that female objectification and self-objectification play in contributing to the prevalence, proliferation, and perniciousness of patriarchy. However, understanding these realities is important because it conveys not only the necrotic intent and outcome of male domination (which is to reduce thinking, feeling, sentient beings into robotic, near-dead objects who exist to be appropriated and abused), but the reality that, in order for patriarchy to become operative and effective, women and girls must be coerced into obedient compliance through a series of socialization processes which normalize their degradation and dehumanization. In this article, I provide a few theoretical frameworks through which the process of female objectification has been understood before analyzing a literary context in which the reduction of women to objects through socialization processes becomes operative. I conclude by demonstrating the contiguous relationship that exists between objectification/self-objectification and male supremacy’s core tenet: rape and sexual assault.

Many individuals–both intellectual and not–have pointed out that the world is predicated upon patriarchal principles which include the ongoing objectification of women. These assessments are important because they enable individuals to move beyond the amorphous, ambiguous realm of being only vaguely aware that something is awry with respect to how women are being conceptualized and treated; with theoretical assessments regarding the reality of female objectification, individuals can think critically and clearly about both what is happening with physical representations of women in material reality and why. In her own conceptualization of the patriarchal lens of viewing that people are told to adopt upon gazing at women, Laura Mulvey asserts that

In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split

between active male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects

its phantasy on to the female figure which is styled accordingly. In their

traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed,

with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can

be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Women displayed as sexual object is

the leit-motiff of erotic spectacle: from pin-ups to strip-tease, from Ziegfeld to

Busby Berkeley, she holds the look, plays to and signifies male desire. Mainstream

film neatly combined spectacle and narrative…The presence of woman is an

indispensible element of spectacle in normal narrative film, yet her visual presence

tends to work against the development of a story line, to freeze the flow of action in

moments of erotic contemplation. This alien presence then has to be integrated into

cohesion with the narrative. (808-809)

Here, Mulvey explores the role that the processes of objectification and self-objectification play in the perpetuation of patriarchy within the film realm, explaining that women are represented as passively posing to generate an erotic impact on male viewers in this domain of reality. Perhaps interestingly, Mulvey accurately identifies this process as creating and contributing to the othering of women when she states that the representation of woman as an erotic spectacle constitutes the incorporation of an “alien presence” into the film narrative. This “alien presence,” she argues, has to somehow be integrated into the narrative flow of the film such that the representation of female people as eroticized objects doesn’t merely exist as an unrelated, irrelevantly agrestic aspect of the story which interrupts its logical, sequential flow. In her analysis, Mulvey conveys the role that the film industry plays in contributing to the production and proliferation of images of women as the site of erotic contemplation for men, thereby conveying the presence of the process of objectification (men reducing women to objects) and self-objectification (female models consenting to being presented as objects).

Like Mulvey, John Berger provides thinking individuals with an ideological framework in which to conceptualize the way

One might simplify this by saying: men act and women appear. Men look at

women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only

most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to

themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed female.

Thus she turns herself into an object – and most particularly an object of

vision: a sight (46, 47).

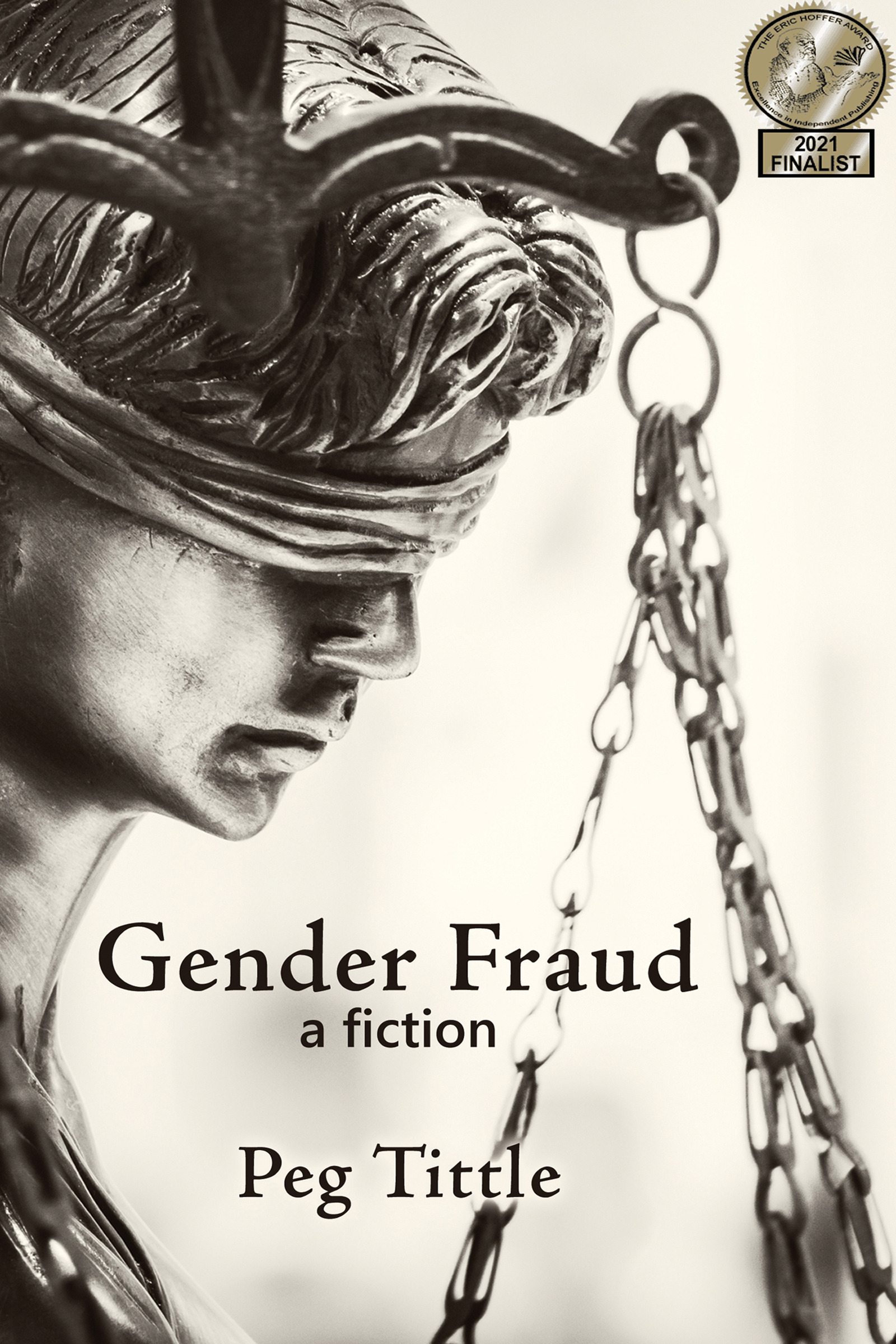

Here, Berger conveys the elements of objectification and self-objectification by demonstrating that women exist as objects for men to look at (objectification) while, in becoming cognizant of this androcentric process, female people then turn themselves into visual objects to be looked at (self-objectification). As may become evident to the reader upon reviewing this section of Berger’s text, male domination works through multifarious systems, almost all of which are malevolent and malicious, working together to create an increasingly narrow, limited worldview for women and about women. Specifically, women are trained to see themselves through a very parochial lens and society as a composite whole is taught to think of womanhood in increasingly narrow ways. This reality becomes evident both in the realms of reality which guide our daily life as well as the fictional worlds of literature which reflect key aspects of these worlds. In the fictional world of Peg Tittle’s Gender Fraud, for example, central character Katherine Elizabeth Jones is arrested for the crime of Gender Fraud, meaning that she, as a female person, has violated the law by engaging in behaviors deemed inappropriate for women, some of which include wearing men’s clothing, not wearing make-up, maintaining short hair, remaining unmarried and not having children, and pursuing an advanced academic degree (11, 12). As a result of these “crimes,” Jones is placed in a psychiatric facility for the purpose of being cognitively and somatically trained to conform to the parochial, patriarchal script regarding how women should think and act. Within the limiting confines of the psychiatric facility, Jones is exposed to literature which reinforces the patriarchal program’s plan for women. While waiting to be seen by the psychiatrist, she glances “at the magazines on the low table in front of her. Cosmopolitan, Vogue, Good Housekeeping, Better Homes and Gardens. They were really pouring it on. Then again, she realized, those were exactly the magazines every doctor’s office would have. And every dentist’s office. Every government office…” (70). Here, the reader becomes aware of the protagonist’s consciousness that the same literature being used to promote patriarchal propaganda within the psychiatric facility in which she is confined is utilized to advance androcentric ideologies in the real world that exist beyond the training center where she is being taught to comply with limiting edicts regarding what female personhood can incorporate.

When considered carefully, it becomes clear that the concepts depicted in the magazine content reinforce the understanding of women operating within the framework feminists have identified within terms of sexual and/or reproductive labor being the primary mediums through which female people are used within the patriarchal system. Within magazines such as Cosmopolitan and Vogue, the concept of women existing for the purpose of sexual labor is reinforced by cover images of female people operating as the erotic spectacles Mulvey wrote of in “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Ariana Greenblatt provides the cover photo for the Winter 2025 issue of Cosmopolitan and is featured wearing a pink bra with black lace and lacy stockings which make multiple regions of her body, including much cleavage, viewable for the observer. Similarly, Emma Stone creates the cover image for the September 2025 issue of Vogue, in which she wears a decorative black jacket-like topic which leaves her belly button and lower abdominal region exposed. The message conveyed through the patriarchal propaganda produced by the cover images of Cosmopolitan and Vogue is clear: woman equals sex.

Like Cosmopolitan and Vogue, magazines such as Good Housekeeping and Better Homes and Gardens purport patriarchal propaganda by reinforcing specific messages which bolster androcentric ideology. While Cosmopolitan and Vogue promote the idea that woman equals sex, Good Housekeeping and Better Homes and Garden purport the idea that woman equals breeder and she loves the cult of domesticity. In the December 2025 cover of Good Housekeeping, for example, the feature image is a cluster of boxes which female hands are arranging. The wording for the magazine cover includes “Cookies, Crafts & Cocktails for Good Holiday Cheer!” The cover also advertises the “2026 Kitchen Awards” and bakeware, toothpaste, olive oil, blenders, hair tools, and knives that were subjected to scrutiny and testing as topics that will be discussed within this issue of the magazine. These images and wording teach women, the people to whom this magazine is heavily advertised, that placing primacy on the decorative aspects of life, including home maintenance, play an integral role in facilitating happiness, normalcy, and cultural acceptability. Similarly, the December 2025 issue of Better Homes & Gardens features a display of flowers sitting atop a bureau with the nearby linguistic sequence “Your Happiest Holidays Start Here.” As noted in their own description of their magazine, the purpose of Better Homes & Gardens is to provide home inspiration, recipes for special occasions and everyday use, and garden knowledge for the purpose of enabling readers to create their dream homes. Thus the patriarchal point of both Good Housekeeping and Better Homes & Gardens becomes plain: naturalize the processes of continually redirecting female attention to home decor and maintenance so that the cult of domesticity, along with all other aspects of the patriarchy, may go on with seamless continuity.

When the feminist reader considers the magazines that are found in the waiting room of the psychiatrist’s office that Kat Jones finds herself in, several realities pertaining to objectification and self-objectification become plain. One of those realities is that both principles are made evident and prevalent through the Cosmopolitan and Vogue covers. Specifically, female people are groomed and socialized to believe that they can and should desire to operate as sexualized spectacles for male titillation, thereby conveying the aspect of objectification which involves being treated as a non-thinking thing that exists for a male being or multiple males. They subsequently adopt this non-sentient identity, internalizing it as the desirable mode of seity to embody in the process of self-objectification which becomes evident through the sexualized posing depicted on the magazine covers. Another reality pertaining to objectification and self-objectification which becomes plain through consideration of the magazines that exist within the psychiatrist’s office is that sexualized objectification and self-objectification do not operate in isolation as aspects of the androcentric dystopia; rather, they exist within a continuum of multifarious oppressions which work to reinforce the idea that women can and should be tracked into specific life patterns which are consonant with male domination. The Good Housekeeping and Better Homes & Gardens magazines make this reality plain by emphasizing that female existence and agency should be utilized for the purpose of participating in the cult of domesticity, with this aspect of energetic use operating in consonance with the patriarchy’s purpose of reducing women to wives and mothers whose primary function is to breed and maintain aesthetically appealing homes. The astute reader should thus note that these magazines are not necessarily randomly clustered together within the psychiatric office; rather, their placement is designed to connote that women must either exist as sex or as homekeepers.

In further considering the patriarchal implications of Good Housekeeping and Better Homes & Gardens, one might argue that the magazine placement, which includes clustering propaganda regarding female people operating as sex or homekeepers together, functions to show women that they may intermittently choose to exist as eroticized spectacles and keepers of houses, with this reality working to create the illusion that the patriarchal world offers women a plethora of meaningful choices which are confluent with cognitive and somatic expansion or freedom. This is how the reality of androcentric dystopia can be transformed into a utopia within the mind of the observer; to paraphrase, this is how systems akin to slavery purport themselves as systems of freedom such that individuals observing them conclude that they are desirable and ideal.

Recently, I listened to a radical feminist discourse which involved one contributor asserting that, contrary to the idea that some women are aware of patriarchal patterns while other female people remain fundamentally unconscious of its pernicious structure and systems, each woman understands what androcentrism is about. I now disagree and rather believe, in accordance with many other radical feminists, that what the majority of women tend to do is maintain an aggressive will to not know what they already know about patriarchy for the purpose of avoiding conflict, attaining social privileges, and finding “love” within the heteronormative confines of dating, marriage, and sexuality. This is probably why female consumption of patriarchal propaganda such as Cosmopolitan and Vogue remains significant; it is not because women don’t understand that consuming these mainstream/malestream forms of media contributes to the reproduction of patriarchal principles such as objectification and self-objectification. Rather, it is that inundating one’s mind in these androcentric realms enables the reader to keep forgetting and keep not remembering what is really going on within the patriarchal program: the rape of women and girls. Thus another thing that is important to remember is that the production and proliferation of male supremacist forms of media which promote objectification and self-objectification is not divorced from the reality that sexual assault is the core of the patriarchy; rather, the creation of these mediums functions as a distraction from the cultivation of awareness regarding the normalization and perpetuation of rape as an integral, acceptable aspect of female existence. In conclusion, radical feminists must remember to recognize the interconnected nature of all things under patriarchy such that we collectively resist objectification and self-objectification as demeaning practices which both 1. dehumanize women and 2. deflect attention away from other egregious aspects of male supremacy such as sexual assault.

Dec 29

What Is The Purpose Of Radical Feminist Reading, Writing, And Thought? (Part 4 of 4) by Jocelyn Crawley

Unlike much of the discourse that transpires in the living world, radical feminist reading, writing, and thought is not about shallow engagements, conversational pastimes, aligning with power structures, reactionary politics, and/or the development of superficial relationships. Rather, radical feminism is purposeful; the purpose of radical feminism is to end the violent tyranny (which is exacted through both physical force and psychological warfare) against women and girls by men and boys. This purpose suggests that, when women and girls reach the realization that they no longer want to center men and boys in their lives given that doing so makes them susceptible to violence, they will need to rebuild their lives in a manner marked by the acquisition of new cultural proclivities. This is why radical feminist reading, writing, and thought is important. These modalities provide women and girls with the tools necessary to begin to envision a world in which their existence is not predicated upon submitting to male domination. Moreover, radical feminist reading, writing, and thought provides women with the tools through which to understand that this system of male domination is indeed the foundational principle of life in both the historical and modern worlds. By helping women and girls see what is really going on (and what is really going on is the perpetuation of male supremacy), radical feminist reading, writing, and thought enables women to 1. decide if they agree with the subordinate positions of degradation and dehumanization that they have been given under the current regime of domination and 2. determine whether they want to begin to cultivate lives in which they can be and continually become fully human rather than regularly subjecting themselves to the devolution and diminishing that the dominant order insists that they adhere to.

Reading, writing, and thinking in radically feminist ways does not, as many know, end patriarchy. In fact, as one of my former professors noted in discussing the impact and response to the publication of dissident thought, many individuals and institutions that seek to perpetuate systems of domination prefer that these publications happen. When publication of nonconformist thought transpires, people who purport systems of domination can actively monitor what is being said and thought by radicals who may be strategizing to annihilate or at least trouble the system. In recognizing this reality, it is important for radicals to understand that responding to the monitoring of oppressors with the cessation of publication of anarchic thought is not an effective solution. Alternatives would include the privatization of publications, meetings, and radical discourses, the process which is oftentimes referred to as going underground in activist communities. Going underground is a somewhat effective solution for the issue of how subjugated people will operate within the patriarchy’s system of dominative containment given that it enables individuals to speak freely about and strategize against the oppression that they are experiencing. However, it is important to understand that male supremacy is a ubiquitous entity which gains actualization through the brains and bodies of sentient beings; this means that we will never escape it as long as living people consent to its edicts. Yet the inescapability of patriarchy does not have to entail passively acquiescing its existence and awry agency while internalizing its discriminatory logic. Rather, we should regularly produce and circulate counternarratives so that we are not consistently inundated in the fallacious logic which, over time, might convince us that nothing is really wrong and being raped, murdered, subjected to sexual harassment, ridiculed for not dressing “sexy” enough or avoiding intimacy with men is just “the way things are.”

Male domination and all of its ugly affects and effects have not gone away. From racialized rape to the perpetuation of multiple forms of male violence which result in death and other life-negating outcomes, men and the women who support them1 are continuing to inundate everyone in a world of multifarious miseries. As such, it is imperative that radical feminist reading, writing, and thinking continue to exist in antagonistic relationship to androcentric thought and praxis. Although it is clear that the majority of the populace will continue to support the maintenance of male supremacy through active participation in its institutions and cultural productions, radical feminism creates the conditions necessary for individuals to escape patriarchy’s malefic clutches and develop a life of dissident dissent which involves happily struggling towards the attainment of autonomy and full humanity as the system of domination continues its work of dependence and dehumanization.

*

Radical Feminist Must Reads (Fiction, Non-fiction, and an Essay):

Complaint! by Sara Ahmed

Intercourse by Andrea Dworkin

Where We Stand: Class Matters by bell hooks

Only Words by Catharine MacKinnon

The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

The Dialectic of Sex by Shulamith Firestone

Amazon Odyssey by Ti-Grace Atkinson

Female Erasure: What You Need To Know About Gender Politics’ War on Women, the Female Sex and Human Rights by Ruth Barrett

“The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House” by Audre Lorde

Dec 22

What Is The Purpose Of Radical Feminist Reading, Writing, And Thought? (Part 3 of 4) by Jocelyn Crawley

Once one becomes a radical feminist or even a feminist, one often recognizes the danger of continually immersing oneself in systems, structures, and societal groups that are predicated on the intentional or unwitting collusion with the patriarchy. Yet the problem is that because the world is organized around patriarchy as the foundational, primary, and only acceptable culture, finding a radical feminist counterculture can be challenging. However, it doesn’t have to be thanks to radical feminist readings, writings, and thought. For example, numerous radical feminist organizations, including Women’s Declaration International, have developed a culture in which women can gather and discuss our dissident and dangerously ungovernable ideas. WDI hosts a show called Feminist Question Time on Saturday mornings for the purpose of discussing key issues that are impacting women such as the perpetuity of pedophilia and the perpetuity of sexual assault. WDI also produces videos that are organized around meaningful topics. In many cases the content produced by WDI includes discussion and mentioning of important radical feminist texts, and this reality helps us understand that the anarchic, non-assimilationist ideas produced by radicals are positively impacting the world by contributing to the development of countercultures in which women can engage with one another in non-patriarchal ways which do not involve them subjecting themselves to the multifarious forms of degradation and dehumanization that they would experience in virtually any other setting that unfolds in material reality.

Similarly, WOLF (Women’s Liberation Front) is a radical feminist organization that places primacy on the liberation of women and girls from patriarchal domination. In addition to hosting a plethora of women-centered events that involve actively fighting against male supremacy, WOLF hosts weekly virtual coffee meet-ups in which women can gather and discuss key feminist issues. These events are organized from a radical feminist perspective, and organizational leaders such as Lierre Keith avidly read texts from within this ideological milieu and can be seen collaborating with other radical feminist thinkers in contexts where the works of women writers are subjected to intense and meaningful analysis. That the thought processes of WOLF’s organizational leaders is deeply informed by radical feminist ideologies is important because it shows us that, as opposed to prototypically patterned patriarchal organizations whose male leaders value traditional, non-progressive ways of doing things (such as non-inclusion and unilateral decision-making), there are feminist organizations whose representatives remain grounded in practices that are adamantly opposed to the patriarchal norms which perpetuate sexism and the protection of narcissistic interests.

Dec 15

What Is The Purpose Of Radical Feminist Reading, Writing, And Thought? (Part 2 of 4) by Jocelyn Crawley

Once you realize that patriarchy is effective in part because it is built on lies, or false narratives regarding what reality is and how it should be, it is important to develop a counternarrative. This is a second reason for reading radical feminist work. Although defined diversely, counternarratives are basically responses to the dominant narrative and its inaccurate, inappropriate representations of reality. Counternarratives exist to challenge the logics of domination which come to constitute the normal way that people interpret reality. Dominant narratives, which are also narratives of dominance insomuch as they reinforce the power that men have over women as well as the view that this is how things should work, exist in every sector of society and function as patriarchal propaganda designed to produce compliant, docile female citizens who accept male supremacy. Furthermore, dominant narratives are the prevailing interpretation of reality, meaning that they tend to shape society’s understanding of how we should think about our identities and events that take place in the material world. Dominant narratives are reinforced through the process of repetition, meaning that they are told over and over again so that they are normalized in the psyches of those who are exposed to them. These narratives are amplified by all types of media sources, including the film and music industries. Additionally, dominant narratives typically marginalize the experiences and ideas of historically oppressed people while also suppressing, ignoring, or ridiculing alternative viewpoints.

An example of a normal dominant patriarchal narrative would be “A wedding is the happiest day of a woman’s life. She is given away to her husband by a loving father, and this process symbolizes her newfound immersion in the realm of adult love and blissful sexuality which she will experience in the arms of a loving man.” A feminist counternarrative would be “Weddings function as an arm of the patriarchy which convey that female people are transferred as property from one man to another; the wedding will be the onset of the saddest, most miserable days of the woman’s life as she becomes inundated in a realm of non-orgasmic sex, verbal abuse, and emotional immaturity.”

There is a plethora of other counternarratives that women have devised in order to refute the erroneous logic of patriarchy so that they can start thinking in divergent ways which gravitate away from male supremacy and towards the conceptualization of female people as fully human. These counternarratives help dispel the lies of dominant narratives, many of which are told in simple, mantra-like formats (because the slogan-style form of language use can make concepts easier to remember). One dominant narrative-slogan designed to promote the aspect of male domination which involves the legitimization of rape is “No means yes. Yes means anal.” This verbage advances the patriarchal view that women do not have the right to say no to male sexual advances (which actually become rape rather than anything “sexual” because consent is absent when an individual cannot say no to unwanted sexual activity) while also conveying that when a female person consents to one form of sexual activity, the male is entitled to pursue other forms of bodily engagement without attaining permission. Feminists (as well as individuals who do not explicitly align themselves with feminist values) have developed many counternarratives which combat the presence and perpetuation of male supremacist logic as made evident in statements like this. One such counternarrative is “No means no.” Rather than adopting the logics of domination and its insistence in the normalization of removing a woman’s ability to say no to unwanted “sexual” activity, groups such as the Canadian Federation of Students are advancing the view that consent is mandatory and must be taken seriously. The seriousness of the “No means no” counternarrative has been historically advanced by the organization of annual events such as Take Back The Night. Originating in the 1970s, this annual event emphasizes the importance of recognizing sexual violence as an egregious harm which must be actively and arrantly resisted.

Another dominant narrative of male domination is that patriarchy does not exist; rather, women “protest too much,” imagine that they are being discriminated against when they are not, don’t understand that men ruling the earth and women submitting to their rulership is God’s plan and deviation from it is demonic rebellion, will simply not accept their nature-based inferiority and accept their lot in life, etc. Additionally, the dominant narrative “patriarchy does not exist” is not always rooted in the aforementioned understandings; it can be rooted in the misperception that patriarchy may have existed in previous eras, but the passing of time has resulted in the revolutionary and/or progressive evolution necessary to ensure that women and men are treated equally in our contemporary period. Therefore, the “patriarchy does not exist” concept is a two-fold master narrative that is rooted in either ignorance regarding the ongoing war against women or a desire to shut women up so that they will keep going along with patriarchal edicts. Radical feminists have been producing effective counternarratives to these lies for quite some time. One such counternarrative is “I’ll be a post-feminist in post-patriarchy.” This counternarrative works to undermine the lie that patriarchy does not exist while simultaneously asserting that feminist antagonism towards male domination will continue until male supremacy is no longer an active, operative component of the material world. Thus, by asserting that patriarchy does exist and subsequently asserting that there therefore is a need for feminism, the slogan “I’ll be a post-feminist in post-patriarchy” functions as an effective counternarrative to the dominant mantra of pretending that patriarchy is either 1. not real or 2. existing but not a problem but rather the appropriate, acceptable way that reality should work.

Dec 15

Roar and Dickinson (both on AppleTV)

Roar is a disappointment–to see what passes for feminism these days, you’d think it was the 1950s (a feminist moment is realizing that being an object of beauty on a pedestal is not a fulfilling life? seriously?).

But Dickinson is a hoot and I’m loving it–it might not be historically accurate, but I think Dickinson would approve because the creators are telling the truth, they’re just telling it slant.

(both on AppleTV)